By Claire McNear

Getty Images/Ringer illustration

The obvious thing, really, was that the man in the fedora was a magician.

I would have known this if I’d seen him on the street or the subway, or shopping for zucchini at Key Food. I would have known if he, fedora-clad and decked in silver jewelry like a latter-day Criss Angel (add to notes: Was this actually Criss Angel?), had strode into view of my dentist’s chair in the last woozy seconds before I drifted off. But I know this beyond thinking, beyond suspecting, beyond fact-checking-your-mother’s-love certainty, because he, like me, had chosen to spend a Tuesday night at a magic show. And also because he told me. Kind of.

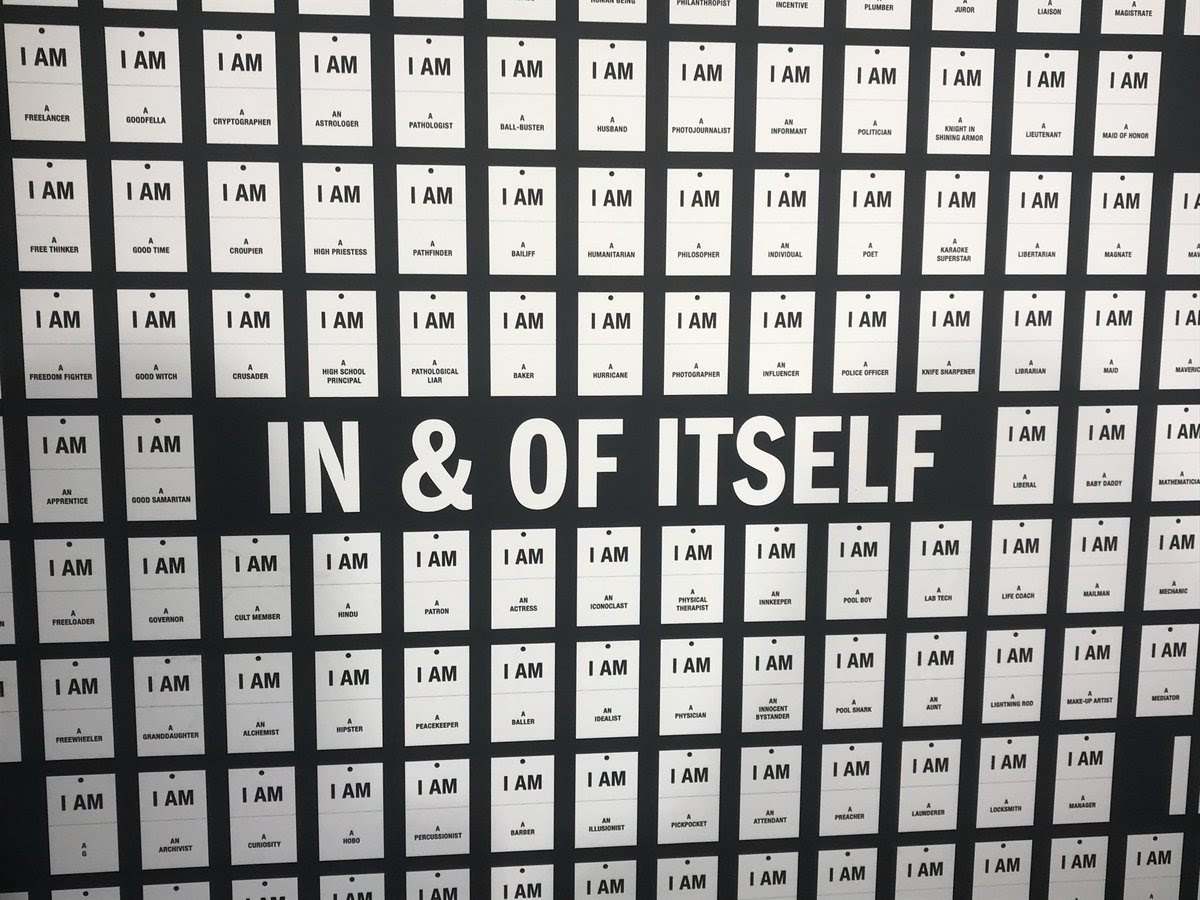

I was in the entry gallery of New York’s Daryl Roth Theatre, where a springtime show of In & of Itself was about to begin. Visitors on their way in to see the acclaimed solo production of the magician Derek DelGaudio were first led here, to a grid of 1,000 paper stubs arranged across a wall, each beginning with the words “I AM” and then offering a potential identity: everything from the literal (“journalist,” “woman,” “daughter”) to the potentially absurd (“idiot,” “narcissist”). Audience members are told to take one and then proceed to their seats.

Rebecca Haizmann

@RebeccaHaizmann

And so there were some other things I knew about my fellow visitors—for one, that the woman sitting a couple of rows away was Jewish: “I’m a Jew!” she exclaimed when she saw what would become her card on the wall. A man in a wheelchair studied his options, chuckling at the prospect of proclaiming himself “AN OLD BASTARD.” The “I AM AN ILLUSIONIST” card disappeared from its peg. So had the man in the fedora.

By the end of the night, an elephant had appeared, and you might have found yourself, as I did, grinning like a lunatic when a prop sheathed in playing cards vanished, seemingly into thin air. The odds are also good that one bewildered member of the audience will be reduced to laughter or tears, or laughter and tears, onstage. It is not your typical magic show.

Which is just as well: The magician at hand insists he isn’t doing magic at all. “Is it?” DelGaudio asked me, coyly, when I suggested to him that the show might be, at least in part, about illusions. He is fond of calling the production an existential crisis, and it is perhaps more easily thought of as a work of theater, anchored by DelGaudio’s autobiographical monologues.

For DelGaudio, the problem with a magic show is the thing most would consider elemental: the tricks. “Traditionally, at most magic shows, people leave saying, ‘How did he do that? That’s amazing. I don’t know how he did that,’” DelGaudio told me. “That’s the thought that 90 percent of the room probably has leaving.”

This is DelGaudio’s challenge. How do you stop the audience from thinking about magic as a series of riddles to be solved? Or, more specifically: Can you be so good at magic that you stop people from thinking about the magic at all?

For a long time, when I thought of magic, I pictured Gob Bluth. I’d seen the odd shell game crowding a sidewalk and the occasional caped performer at childhood birthday parties, but it was Arrested Development’s ne’er-do-well brother who seemed to encapsulate the art form best: something self-serious and overwrought, a cartoonish spectacle where tricks played second fiddle to outlandish personas. Once, I saw a chain-mail-clad David Blaine electrocute himself on a pedestal over the Hudson River in the midst of a continuous three-day stunt. I thought, mostly, about what he did when he had to pee.

The Daryl Roth Theatre is cozy, with 150 seats arranged in a dozen-odd rows above a spartan, ground-level stage—which, for the record, you will be sharply scolded for mistakenly stepping on, giving the impression that some hidden lever or drop to the basement is maybe hidden under an unmarked board. Or maybe not.

“The thing I was most interested in wasn’t tricks,

it was sleight of hand. It was this idea that there

are these invisible mechanics that you could learn

to create astonishing moments.”

DelGaudio’s set is simple, with just a handful of props and a small table to the side. He makes a habit of leaving it to walk up the aisle and into the crowd. He stands, at times, just inches from audience members, occasionally locking eyes with them, and the show has a way of becoming mutually revelatory, with the sort of eased confidences that more often come late at night with close friends and wine.

The show’s identity cards have become the production’s hallmark and a popular keepsake in the way that the similarly audience-involved production Sleep No More’s ghostly white masks were several years ago—so much so that they’ve inspired imitators. Organizers of a Sundance Film Festival event that used nearly identical cards in January were forced to apologize when some of In & of Itself’s more prominent fans, including comedian Patton Oswalt, NPR’s Peter Sagal, and author Neil Gaiman, cried foul.

These days, any number of things might bring you to DelGaudio’s show. You might have heard about the sellouts, the five extensions in Los Angeles and this latest, the fourth and final, in New York. Or perhaps you caught wind of the entertainment bona fides of the show’s creators: It’s directed by Frank Oz, of Muppets and Star Wars fame, and scored by Mark Mothersbaugh, of Devo; the New York leg was produced by Neil Patrick Harris and Tom Werner, the chairman of the Boston Red Sox and Liverpool F.C., who also happens to have TV production credits ranging from The Cosby Show to 3rd Rock From the Sun to That ’70s Show. Maybe it was the rave reviews from the many celebrity admirers who’ve clamored for a seat: Stephen Colbert and Barbra Streisand and Mark Hamill, who declared on Twitter after his viewing that he had “never seen anything like it & it will remain with [him] forever.”

Possibly, you read that the baby-faced DelGaudio, who is 34, is a generational talent, the two-time Academy of Magical Arts Close-up Magician of the Year and 2016’s all-around Magician of the Year, the sort of performer whose name already fills message boards with varyingly plausible tales of I knew him when. Or maybe you didn’t know about any of that and simply saw the word “magic” on a marquee off Union Square and thought—well—why not?

And yet In & of Itself’s magical set pieces are few and far between. At a typical magic show, audience members might be called upon to volunteer themselves to be sawed in half—something DelGaudio executed a twist on with the actress China Chow in 2011 in a show called “A Walk Through China.” Audience members were invited to stroll between the ostensibly bifurcated Chow’s segments. Here, in his most recent show, the involvement is subtler and deeper, more emotional. “I’ve had people sitting out front of the theater sobbing after the show,” DelGaudio said on Pete Holmes’s podcast last year.

Bruce Glikas/FilmMagic

The afternoon after I saw his show, I sat down with DelGaudio by the replica card wall located under the main theater, a decidedly more selfie-friendly location for visitors. He had been performing six days a week, with two shows on Saturdays and Sundays. Since the show moved to New York, he had been living around the corner from the theater, and he turned up to our meeting in a T-shirt and cardigan. Later that night he would don the dapper three-piece suit that he wears during each show, heightening the sense that he might have wandered directly out of the Gilded Age. More than two years into the bicoastal run, DelGaudio was ready for this final extension to wrap up in August; when I asked him if he knew what might come next, he deadpanned, “I definitely need to sleep for a while after this is over.”

In & of Itself is a show about identity—DelGaudio’s and the audience’s. The performance is roughly structured around a series of vignettes about DelGaudio’s life; the identity cards are meant to get the crowd thinking about the contours of their own. The night before, I had selected the “brick house” card as a nod to my family, which runs a brickyard in Northern California. Audience members sometimes got far more serious. At one show, DelGaudio said, a woman ended up confessing the intricacies of her romantic life to the crowd, revealing that the man she was sitting with wasn’t her husband. “She and her lover were having an affair,” said DelGaudio. “They confessed it on stage to the room and told us that we were the only people they could tell, and that they wanted to tell their friends and family, but they couldn’t for fear of judgment.”

For DelGaudio, the autobiographical is also magical. When he was 12 years old, he walked into a downtown Colorado Springs magic shop called Zeezo’s, looking to purchase materials for a practical joke he wanted to play on his mother, who was raising him on her own. Instead, the man working behind the counter offered to show him some magic. He took a pocket knife in his palm and closed his hand. When he opened it again moments later, the knife was gone. The young DelGaudio was thunderstruck and told the man that he wanted to buy whatever it was that he had just seen. The man said it wasn’t for sale, and that he would have to learn it from a book.

“That was the first time … I experienced magic versus a trick,” said DelGaudio. “And a moment of real wonder. I knew there had to be some sort of method behind it, but I didn’t care. I just thought it was pure, and that feeling struck me. And the thing I learned that day was that the thing I was most interested in wasn’t tricks, it was sleight of hand.

“It was this idea that there are these invisible mechanics that you could learn to create astonishing moments.”

DelGaudio fixed his attention on the book he got from Zeezo’s: S.W. Erdnase’s The Expert at the Card Table, something of a sacred text in card-manipulation and sleight-of-hand circles. The teenage DelGaudio mastered one move—called an “effect”—after another. He became a regular at Zeezo’s, imploring older magicians who passed through to teach him more and taking Greyhound buses to catch performances. “A lot of people I had to seek out, because the people who do these things professionally—at least card mechanics—they’re not exactly looking to be found,” DelGaudio recalled. His home life was rocky: His mother, a firefighter who came out as gay when DelGaudio was young, faced opposition in their conservative Colorado community and went through an ugly separation. By the ninth grade, DelGaudio had dropped out of school and devoted himself to magic, charming his card-manipulating elders with his determination.

As DelGaudio got older, he noticed how little his non-magician peers seemed to make of his burgeoning mastery. “I showed other people, and they made fun of it,” he said. For them, a magic trick was either disposable entertainment or something to be solved, and nothing more. When DelGaudio was 17, he moved to Los Angeles, where he studied theater at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts. He booked some private shows in his early years in L.A. and found much the same treatment of magic there, with the same indifferent audiences.

“That’s a really hurtful thing,” DelGaudio said, “to love something and value something and then find out it has no value in the world.”

He was beginning to make a name for himself with sleight of hand—the first trick he remembered learning was the Three-Card Monte, often considered the quintessential con game—and he figured that even if he didn’t perform onstage, he might still be able to make a living off it. DelGaudio was introduced to an underground high-stakes poker ring in Beverly Hills, where a dealer who might be able to work the decks to make sure the house, or, more often, a shill secretly working for the house, came out on top—a so-called bust-out dealer—was in high demand.

“I think that there’s a romantic side of the idea of gambling and cheating in cards,” said DelGaudio. “But for me, when I was young, I fell in love with sleight of hand. Specifically sleight of hand with cards. And particularly, moves that were designed for cheating. That wasn’t because I wanted to cheat at cards. It was because they were the methods that had a utility.”

He had the makings of a formidable card cheat: When he was still a teenager, he mastered the center deal, a notoriously difficult move in which the dealer draws a specific card from the center of the deck. To this he added the basics of hustling to his sleight-of-hand repertoire, each night taking home a cut of the poker haul.

For DelGaudio, bust-out dealing offered its own thrill, because he was no longer simply performing: He had to sell what he did as reality—or else. Those types of tricks, he said, are “typically known as the most difficult types of sleight of hand, because they have to be right. They have to be perfect, and that means natural. And being natural is the most difficult part of sleight of hand, having it look like nothing’s happening.” (If that sounds like a television show, that’s because it could be; DelGaudio sold the story several years ago to HBO.)

But high-stakes dealing came to disappoint DelGaudio. If he’d found people who valued what he could do with a deck of cards, it certainly wasn’t for the sake of a sense of wonder. “And then you have to do a different type of soul-searching, and say, ‘All right, where is the value in what I do?’” DelGaudio said. “‘Do I have any value?’”

By then, he was staging performance art shows called “interventions.” He had continued to frequent magic circles—a 2006 Los Angeles Magazine feature on the Magic Castle, a members-only club (and literal castle) where magic is performed in the foothills of Hollywood, described the then-22-year-old in passing as a “handsome kid” who was “not beyond a showdown.” But it wasn’t until DelGaudio was short on cash that he accepted a gig doing magic onstage again.

“I think most people try and don’t quite reach magic,

they reach a trick. So I think that magic is the thing you

strive to produce in the world, and a lot of times, you fall

short and end up with a trick.”

As he got back into performing, DelGaudio wondered if a magic show could be something more than a parade of tricks that demanded solving. “What drew me back was the idea that magic, generally speaking, isn’t art, but perhaps it could be,” DelGaudio said. “There are certainly artists in magic, and those artists create moments and pieces of art, for sure. But generally speaking, it’s not an art form, because that’s not what it’s usually intended to be. It’s usually meant to be a form of entertainment.”

DelGaudio imagined something different. “You use entertainment as the Trojan horse to actually say the thing you’re trying to say or to point to the thing that you want to point to.”

At the Magic Castle, DelGaudio got to know Neil Patrick Harris, a noted fan of magic and a former president of the Academy of Magical Arts board of directors, which operates the Magic Castle. He also met the magician Helder Guimarães, with whom he eventually partnered on his first full-scale show, Nothing to Hide. Like In & of Itself, Nothing to Hide, which premiered in 2012, was a magic show that went light on conventional tricks. It also employed unusual forms of audience participation, with one trick calling for a volunteer to hide a box somewhere on the Magic Castle grounds. As the show grew in popularity, with celebrities like Ryan Gosling and Eva Mendes attending, it moved to the larger Geffen Playhouse in Westwood, where In & of Itself premiered, in an expanded version that was directed by Harris.

DelGaudio was selling out night after night. But more than that—by layering magic into shows that were only secondarily displays of his formidable skills, he had found a way to make his audiences think about much more than the moment a ten of diamonds disappeared.

As DelGaudio set about devising his second show, he approached Oz with a pitch—to direct—and a promise: In & of Itself would not be a magic show. “I had no interest in magic whatsoever,” said Oz. “If it was only magic, I would have said no immediately.”

Oz and DelGaudio had met years earlier, when Oz went to see Nothing to Hide in New York. After the show, Oz’s wife prodded him to introduce himself to DelGaudio, who has compared his shock at Oz’s nonchalant hello—“Hi, Derek, Frank Oz”—to when he met Muhammad Ali. The two became friends, connecting over the breadth of their respective creative ambitions: Where DelGaudio feared being written off as just a magician, the artistically peripatetic Oz was rankled by descriptions of him as simply a puppeteer. If you give a person a label, Oz says, “I will see you one way, with no layers and no complexity. No humanity.”

“I don’t want to be labeled a puppeteer,” said Oz. “I don’t want to be labeled a comedy director. I don’t want any labels whatsoever, because it’s limiting.”

“You use entertainment as the Trojan horse to

actually say the thing you’re trying to say or to point

to the thing that you want to point to.”

In & of Itself is a multidisciplinary performance, as much theater or performance art as magic. You are lured early on into thinking the only magic you’ll see will be of the stage variety: elaborate props, including a golden composite of DelGaudio’s own face that twists and turns along with his narration. “He’s using the show for therapy,” Oz said in 2016.

we’ll go from there.

we’ll go from there./cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/60206129/clair_magician_getty_ringer.0.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/11611987/GettyImages_880496924.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/11611997/GettyImages_802730728.jpg)